Analysis: In ‘The Dance Before,’ a biography of Samuel Beckett, Gabriel Byrne portrays a man, not a myth.

It would be hard to think of a more anti-modern version of Samuel Beckett than a biopic. An Irish writer who moved to Paris, found inspiration in the French language and became one of the most innovative writers of the second half of the 20th century, he resisted devotion the intensity and depth of emotion that is the basis of historical fiction.

Publicity and self-promotion were frowned upon for this most secretive of writers, who died in 1989. It’s fair to say that he would not have been happy to be the subject of a film. When Beckett heard that he was the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, he fled to a hotel in Tunisia because of his fear of the circus of celebrities. In a short time, he informed the Swedish officials that he was honored with the award but that he would not be able to attend the ceremony.

“Dance First,” James Marsh’s biopic on Beckett shot in black and white by cinematographer Antonio Paladino, doesn’t let these facts stand in the way of a familiar opening. The film opens with Beckett (Gabriel Byrne), dressed as if he is going to a funeral, at the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm. “What a tragedy!” he mutters to his wife, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil (Sandrine Bonnaire), as his literary praises are sung on stage.

Reliable biographical sources suggest tragedy for Beckett’s wife, who did not like the limelight. But screenwriter Neil Forsyth’s setup moves boldly from false realism to unabashed surrealism.

During the break, not to mention the decoration, Beckett storms the stage, grabs the check and begins to clamber up the side wall to escape public scrutiny. When he goes to an ancient place that might be the site of a Greek tragedy or one of his plays, he engages in purgatory conversations with his alter-ego.

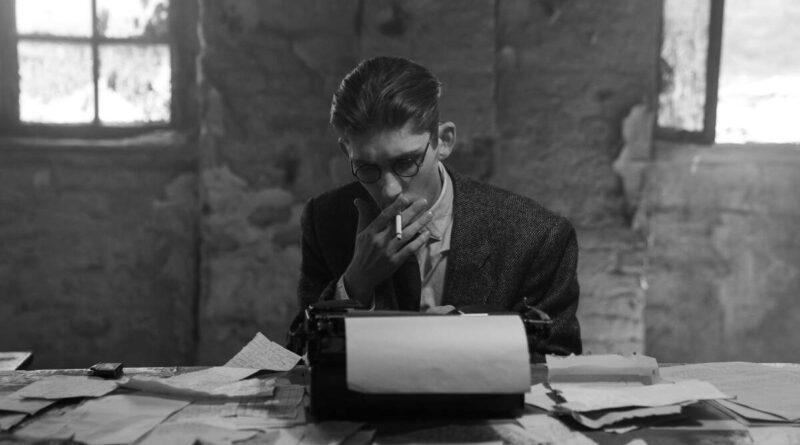

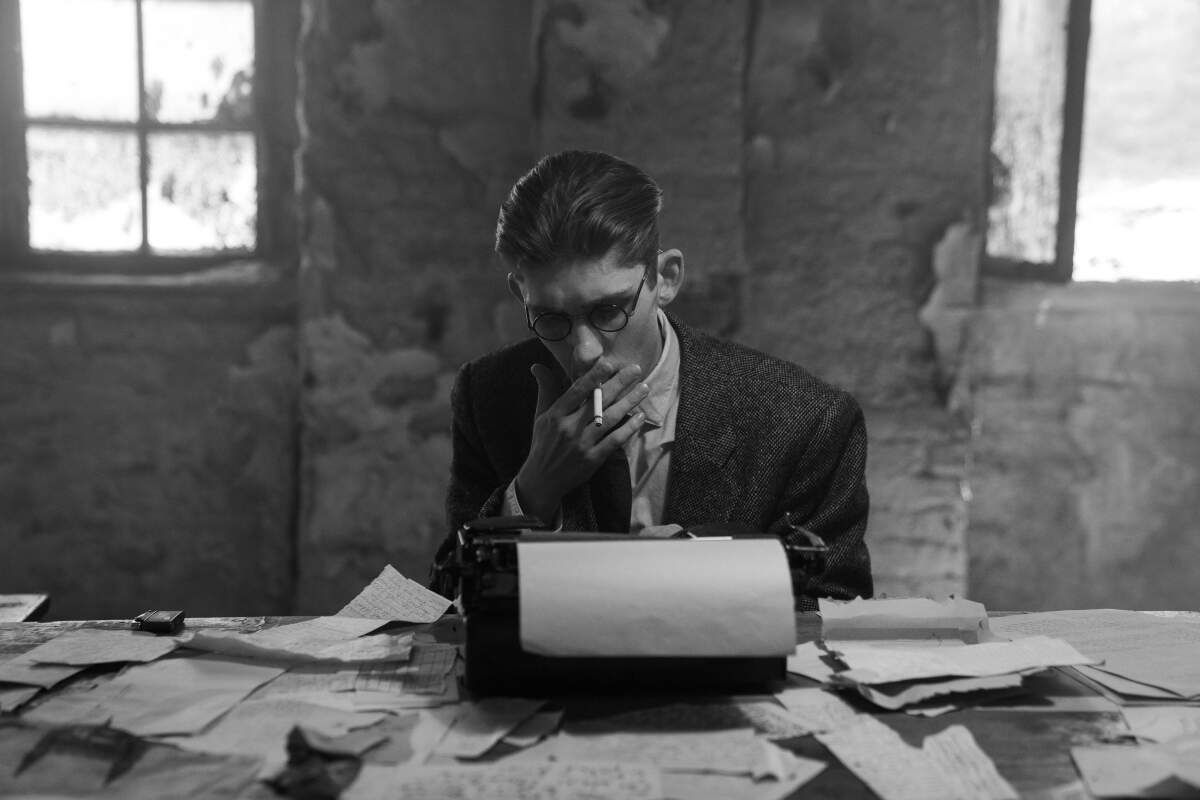

Fionn O’Shea in the film “First Dance”.

(Magnolia Pictures)

Byrne, who plays opposite him, brings these aspects of Beckett’s mind to life in speech. Embarrassed and mortified, Beckett’s uniformed Beckett explains that he accepted the prize so he could give the money. But his energetic and skeptical Beckett asks bluntly, “Whose forgiveness do you need most?”

The film is divided into later chapters on the lovers who appeal to Beckett’s conscience. This framing device, with its unsettling air of mid-game, offers a simple, if unsettling, way to divide one’s life into manageable parts.

The film’s title invokes a line from Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” that puts dance ahead of imagination. But “Dancing First” has little to do with Beckett’s abstract aesthetic.

With his brutal dedication to minimalism, Beckett reinvented whatever art form he was working on. In plays like “Waiting for Godot” and “Endgame,” books like the Beckett trilogy (“Molloy,” “Malone Dies” and “The Unnamable”) and even “Film,” his 1965 screenplay, he abandons work of all unnecessary things, rejecting conventional expectations and finding something to say when all the window dressing has been removed.

The meaning is not sent to Beckett’s work but is created in a perfect sequence of style and content. On the other hand, Forsyth’s screenplay for “First Dance” serves as a container for biography and commentary. There is a literary quality to the film, which provides an overview of Beckett’s life, with all the important moments neatly accounted for.

What redeems the film is the human effort to reach beyond the myth to find the man. Byrne’s Beckett is perhaps no less violent, both outwardly and inwardly, than the popular image of the author. Giving a weary expression, the actor conveys the restless yearning of a self-confessed man, portraying an aging Beckett dragging his corpse to the finish line. Bodily suffering as a constant source of black humor and an oft-repeated metaphor for the human condition in Beckett’s writing, the image of the descent of death remains.

But an air of artificiality hangs over the film, as it continues to present facts. Unraveling Beckett’s journey in a series of fast-paced, self-contained chapters, “The Dance First” can’t help but distort and over-dramatize.

Beckett was known to have a strained relationship with his somewhat disapproving Protestant mother, May (Lisa Dwyer Hogg), the first stop on the guilt trip. of an exaggerated writer. Young Beckett (played with admirable self-sufficiency by Fionn O’Shea) flees Ireland in part to slip beyond his iron, but the film doesn’t hint at the roles. some of the bonds that would haunt Beckett’s work throughout his career.

An episode about Lucia Joyce (played by Gráinne Good), the mentally ill daughter of James Joyce who convinced Beckett to marry her, and scenes depicting Beckett’s involvement in the Resistance during World War II they are abbreviated in ways that appear to be false. But the actors have moments beyond the recap treatment.

The interactions between O’Shea’s Beckett and Aidan Gillen’s James Joyce, the first counselor who resists the role but is eventually won over by the young man’s tough respect, are intricately handled. Gillen’s Joyce recognizes not only Beckett’s madman but also her daughter’s erratic husband – a plan that empowers his no-nonsense wife, Nora (Bronagh Gallagher), who is more than a little confused by the machinations of home.

Beckett’s isolation, his ability to resist falling prey to other people’s needs, enables him to become a Great Writer, but at a cost that becomes more apparent as the film shifts to Suzanne (played by Bonnaire as a mature woman with Léonie Lojkine as a girlfriend, who pretends to be important, with feelings of love and in a real way to him). Bonnaire and Lojkine maintain not only the player’s dignity but also his far-sighted intelligence and tact.

Suzanne understands the role of being Beckett’s wife, guarding against anything that could interfere with her higher mission. It is not clear that Beckett would have realized his gifts without the stability he provided. He was faithful, after his fashion, to the woman who was at his bedside while he was recovering from a near-fatal beating in an unprovoked incident of street violence in 1938. He has and him with love and courage during their dangerous years of war they are working. by Resistance.

When Barbara Bray (Maxine Peake), a BBC script editor who happens to be Beckett’s long-term mistress, enters the story, Suzanne carefully navigates the treacherous waters of marriage. The pain that Beckett inflicts on both women is silent on his beautiful, craggy face. He may be selfish, but it would be a mistake to think he is heartless.

Language is inadequate to the suffering he inflicted, but Beckett manages to give it artistic form in “Play,” his daring one-act play in which a man, a woman and a lady tell their story of infidelity. warp speed as they are planted in the funeral procession. some permanent after death.

Beckett might have a reputation for being dark, but he was also a sportsman who loved rugby, cricket, tennis, attractive women, male companionship and good whiskey. O’Shea has room to include this other Beckett, but Byrne’s unique style seems more at home in a monastery or an academic library.

However, the acuity of the writer who felt things so deeply that he would not give in to low emotions appeared. “The First Dance” may not be particularly Beckettian, but it is based on a character who, intended for the masses, was unquestionably human – very human.

‘Dance First’

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 40 minutes

To play: Opens Friday, Aug. 9 at Laemmle Monica Film Center, West Angeles; Laemmle Town Center, Encino

#Analysis #Dance #biography #Samuel #Beckett #Gabriel #Byrne #portrays #man #myth